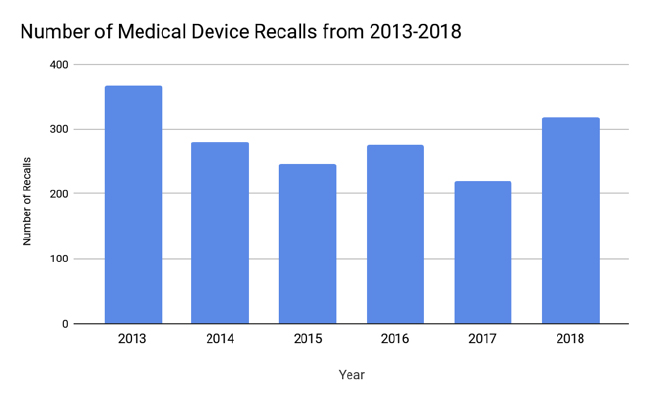

Since the FDA last issued its Medical Device Recall Report covering FY 2003 to FY 2012, changes in the medical device industry have shifted the nature of medical device recalls.1 Our team’s goal was to analyze U.S. medical device recalls from 2013 to 2018 to provide an update on notable trends and lessons that medical device firms can incorporate into their quality and risk management systems. Most notably, software-related recalls are on the rise due to the increasing sophistication of medical device technology. Class I recalls, which pose the most serious risk to public health, have also increased in recent years, although Class II recalls remain the most abundant.2 The FDA recommends that firms issue a press release for Class I recalls and some Class II recalls in order to alert the public of potential risks.3 Unfortunately, recalls can tarnish the public perception of a firm. A 2017 McKinsey Report estimates manufacturers can experience as much as a 10% decrease in shares after a major recall, along with damage to the company’s reputation.4 Therefore, medical device firms should have a comprehensive, integrated quality system in place to both prevent and address recalls. Response plans should be developed in anticipation so that in the event of a recall, firms can act expediently and in accordance with regulations. These plans should be re-evaluated and updated periodically. We hope this article will help stimulate thought about how your firm can update its recall prevention strategy in light of trends from the past five years.

Recall Trend Analysis (2013-2018)

The Stericycle Recall Index was used to examine trends, because it is a comprehensive index that analyzes aggregate data from the FDA.5 An older analysis by Blue Lynx Consulting found that the predominant cause of device recalls from 2010–2014 was device design, followed by software controls and production controls.6 Since then, software issues have superseded device design as the top cause for recalls for the past eleven consecutive quarters.5 An analysis from 2011–2015 identified 627 software related recalls affecting 1.4 million units, with anesthesiology and general hospital as the largest high-risk recall categories.7 This shift reflects the increasing complexity of medical software.

Innovative technology has proven to be a double-edge sword. Although software issues have contributed to an increasing amount of recalls, enhanced tracking technology may assist in efficient identification of affected devices. Examples include unique device identifiers (UDIs), electronic health records (EHRs) and devices with sensors, which can aid distributors and healthcare providers in tracking and identifying affected products and patients.8 A report from Transparency Market Research estimates global medical device connectivity will reach $33.5 billion this year.9 Device connectivity may be beneficial for data transmission across platforms, but it also carries the inherent risk of hacking or unauthorized access to sensitive medical information. From 2015–2018 the FDA released six product-specific safety communications regarding cybersecurity vulnerabilities, although there have no been any known associated patient injuries or deaths with the incidents.10

Innovative technology has proven to be a double-edge sword. Although software issues have contributed to an increasing amount of recalls, enhanced tracking technology may assist in efficient identification of affected devices. Examples include unique device identifiers (UDIs), electronic health records (EHRs) and devices with sensors, which can aid distributors and healthcare providers in tracking and identifying affected products and patients.8 A report from Transparency Market Research estimates global medical device connectivity will reach $33.5 billion this year.9 Device connectivity may be beneficial for data transmission across platforms, but it also carries the inherent risk of hacking or unauthorized access to sensitive medical information. From 2015–2018 the FDA released six product-specific safety communications regarding cybersecurity vulnerabilities, although there have no been any known associated patient injuries or deaths with the incidents.10

In 2018, the top causes of recalls were software, mislabeling, and quality issues.5 The top cause of most units recalled per quarter can vary widely from quarter to quarter since a single large recall can account for millions of units of a device. A single company can also be responsible for dozens of recalls in a quarter, thus causing dramatic fluctuations between the amount of recalls per quarters.

Another notable trend is the steady increase in Class I recalls, the most serious type of recall with the most potential to cause harm to health. The average number of Class I units recalled per quarter in 2016 was 310,158 and in 2017 the average increased to 511,017 units per quarter.5 In 2018, the average number of Class I units recalled per quarter further rose to 50,648,996. However, the average of 2018 was skewed by an enormous Class I recall in Q1 of 2018, which brought 2018’s first quarter average to 186,580,917 units.5

The role of the FDA is an obvious confounding factor when considering changes in the amount of recalls over the years. Are fluctuations in recalls due to firms producing defective devices or the FDA changing its regulatory stance to act more stringently? A 2018 CDRH report stated that since 2007, the FDA has increased its number of device inspections by 46% and increased its annual number of foreign device inspections by 243%.11 Specifically, the FDA has increased its focus on reporting deficiencies regarding 21 CFR Part 806, which is related to firms initiating a voluntary recall, and 21 CFR Part 803, which is related to adverse event reporting. Another factor to consider is industry growth. While it may appear that the number of recalls is growing, the number of medical device firms is also growing. Taking industry expansion into account, the rate of recalls has actually declined.12

Impact on Medical Device Firms

To address the growing issue of software-related recalls, firms should enhance their pre-market testing of potential failure modes. Outsourcing software may also account for the increasing amount of software recalls since purchasers cannot easily make modifications or corrections. Frequent updates and patches may be necessary to resolve potential issues and increase cybersecurity. Firms should develop systems to ensure users are promptly notified of updates and patches and have adequate customer support. Firms may consider utilizing third-party cybersecurity experts to ensure vulnerabilities are managed. Another strategy would be for medical device firms to employ more IT and CS experts to work in-house on the software components of their devices.

The FDA guidance for software validation was issued in 2002. The 2005 “Guidance on the Content of Premarket Submissions for Software Contained in Medical Devices” and the 2017 “Software as a Medical Device: Clinical Evaluation” Guidance, Section 5.4 Clinical Validation of a SaMD, may be useful additional references. A draft 2018 guidance for “Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices” provides direction on cybersecurity specific issues. Updated, modern software validation guidance and premarket regulation is needed to assist firms in the creation and management of compliant software.

From 2013–2018, on average, approximately 52% of recalls affected products that were distributed both in the United States and internationally (at least one other country or territory). Managing a nationwide recall is already challenging and adding the logistics of coordinating international measures can become extremely difficult if well designed systems are not in place. Firms should be aware of country-specific regulatory requirements in advance and keep abreast of any changes. Firms should also have adequate translation capabilities and procedures to locate and transport affected products internationally.

Summary of FDA Published Recalls (2013-2018)

Our team focused on analyzing the device recalls published from 2013–2018 on the FDA’s “List of Device Recalls” page. These 186 recalls were of interest to us due to the previously noted trend of increasing Class I recalls. The majority of listed recalls are Class I (93.3%) with some Class II recalls (6.7%) included as well. From this set of recalls, there are a total of 34 unique product codes. The most common product code is CBK, which represents a “ventilator, continuous and facility use” device and is a class II device. Other common product code are DSQ (Ventricular Bypass), DWF (Catheter, Cannula And Tubing, Vascular, Cardiopulmonary Bypass) and FRN (pump, infusion).

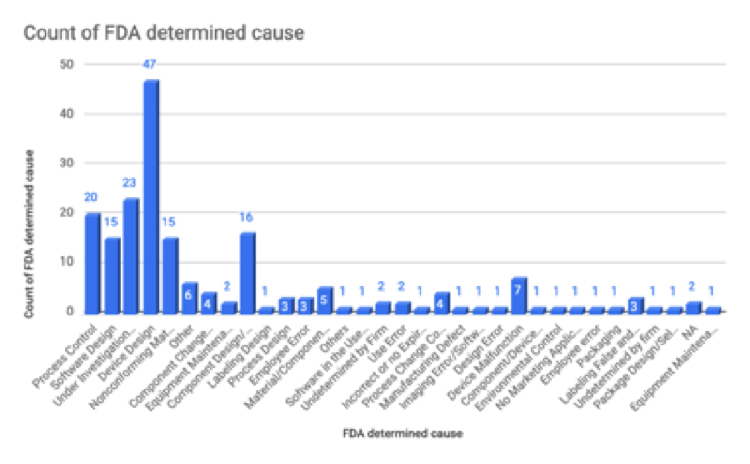

From this set of recalls, device design is the most common FDA-determined cause. The second leading FDA-determined cause is “under investigation” and the third leading cause is process control. Faulty design may stem from insufficient design control during the product development phase. Examples of device design issues include components that do not stay in place, interfaces suspect to user misinterpretation, and inaccurate assays or measuring components. Companies should establish new design control process to ensure proper design review during the design process. The design review will involve the following factors: User needs, design input, design process, design output, and finally creation of the medical device that can meet user needs.

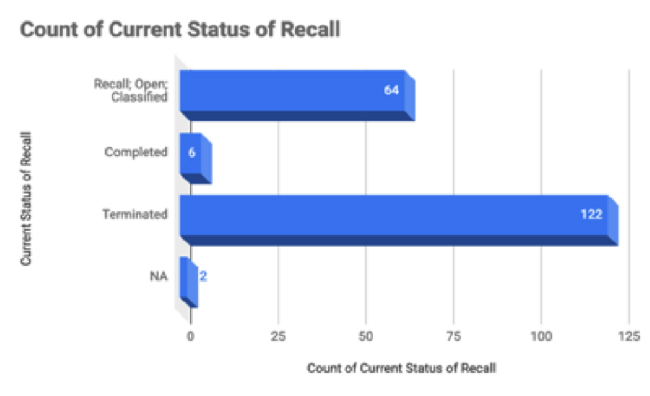

From this set of recalls, 122 of the recalls are terminated and 64 are still open.

Notable Recalls from 2013–2018

In the past five years it has been found that a number of medical devices have been recalled, some were placed back to the market, some were not, and some medical devices were brought to the market after corrections and were again recalled repetitively. Certain medical devices were notable amongst these due to the unique nature of the recall that it faced.

Event Medical LS, 5i, or 7i Inspiration Ventilators: The Event Medical, has been producing inspiration ventilators since March 2000 in the 5i, 7i, LS and 3E types. Out of these products currently the company has three versions of 7i, and a report system device called the Clininet Virtual Report Viewing System.13 On October 13, 2015, the FDA had asked the company to recall all the models of 5i, 7i and the LS variety. Out of all these models, an adverse event of death was reported for the 5i model on January 20, 2015. As per the event report on the FDA website, the ventilator shut down while it was still connected to a patient. The healthcare professional was present during the malfunction and tried to bag the patient and put the patient on another ventilator, but the patient died. This incident was a major reason of the recall, as the device has a life-saving function but failed perform due to device malfunction. The recall was terminated on June 22, 2017 however, the device model never made it to the market.14

Syncardia Systems Freedom Driver system (Artificial Heart): Syncardia Systems issued a Class I recall for their Freedom Driver system due to circuit failure causing the device to stop without any indication. As of August 2015, the company had voluntarily recalled 56 devices, which also included 29 products that were sold in the United States. The device basically is used as a mechanical heart replacement. The FDA issued a recall following the voluntary recall initiated by the company. In October 2016, an adverse event report of a patient dying due to failure of the freedom driver to function was also reported.15

Cook Medical’s Beacon Tip Angiographic Catheter: Since 2015, Cook Medical has been recalling the Beacon Tip Catheter. Royal Flush, Torcon NB Advantage and Slip-Cath are the models that were recalled, with a total number of 95,167 devices being taken off the market. The catheters are used to introduce contrast dye in the vasculature during an angiography. The recall reason was a catheter tip dislodging in the patient lumens, posing a potential health risk to the patient.16

Proactive Steps for the Future

As this article has explained the various aspects of medical device recalls in the past five years, we have a brief idea of some of the key factors behind recalls. Any recall impacts not just the medical device company or patients, but also has an overall effect on the healthcare system and regulatory agencies; it slows down innovation and hinders the financial progress. Over the past five years, much more technologically advanced devices have been brought to market, introducing a higher risk of issues, especially related to software, with medical devices.

These devices must have a unique identification number (UDI), which enables supply chain traceability. Tracking IDs, alarming systems for pacemakers, mobile applications that can track if a device is functioning properly needs to be in place to ensure that devices continue to be viable throughout the given life cycle.

Collaboration and transparency between stakeholders, device companies, FDA and other regulatory agencies, patients and healthcare professionals will ascertain that recalls are more effective and that patient interests are safeguarded to the fullest.

References

- CDRH. (March 2014). Medical Device Recall Report FY2003 to FY2012. Retrieved from https://www.cobalt-chromium-toxicity.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Medical-Device-Recall-Report.pdf

- Mezher, M. (January 10, 2018). Device Recalls in 2017: Making Sense of the Numbers. Retrieved from https://www.raps.org/regulatory-focus/news-articles/2018/1/device-recalls-in-2017-making-sense-of-the-numbers

- Brown, R. (n.d.). Recall Communication: Medical Device Model Press Release. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/training/cdrhlearn/ucm293232.pdf

- Fuhr, T., George, K., & Pai, J. (October 2013). The Business Case for Medical Device Quality. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/dotcom/client_service/Public Sector/Regulatory excellence/The_business_case_for_medical_device_quality.ashx

- Stericycle. (n.d.). Recall Index. Accessed February 17, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.stericycleexpertsolutions.com/product-recall-index/

- Dix, J. R., Ramachandran, S., & Oppenheimer, D. S. (June 27, 2016). What’s Behind Medtech’s Recall Epidemic? Part 1: Device Design. Retrieved from www.mddionline.com/what’s-behind-medtech’s-recall-epidemic-part-1-device-design

- Ronquillo, J. G., & Zuckerman, D. M. (2017). Software-Related Recalls of Health Information Technology and Other Medical Devices: Implications for FDA Regulation of Digital Health. Milbank Quarterly, 95(3), 535-553.

- CDRH. (September 27, 2018). Benefits of a UDI System. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/uniquedeviceidentification/benefitsofaudisystem/default.htm

- Nitin. (May 23, 2017). Home Healthcare Segment to Drive the Demand of the Medical Device Connectivity Market in the Forecast Period. Retrieved from tmrresearchblog.com/home-healthcare-segment-drive-demand-medical-device-connectivity-market-forecast-period/

- CDRHs. (March 01, 2019). Cybersecurity. Retrieved from www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/ucm373213.htm

- CDRH. (November 2018). Medical Device Enforcement and Quality Report. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDRH/CDRHReports/UCM626352.pdf

- Levy, S. (March 21, 2014). Medical Device Recalls Growing at Slower Pace Than Industry. Retrieved from https://www.mddionline.com/medical-device-recalls-growing-slower-pace-industry

- Medical Device Recalls > eVent Medical LS, 5i, or 7i Inspiration Ventilators May Shut Down without Alarm. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.fdanews.com/ext/resources/files/12-15/12-15-eVent-RecallNotice.pdf?1520869159

- MAUDE Adverse Event Report: Event Medical Evolution 3E Ventilator Continuous Ventilator. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/detail.cfm?mdrfoi__id=6813505&pc=CBK

- California Man Dies After Apparent Failure Of Artificial Heart Compressor. (October 20, 2016). Kaiser Health News. Retrieved from https://khn.org/news/orange-county-man-dies-after-apparent-failure-of-artificial-heart-compressor/

- SynCardia Systems Issues Class I Recall of Freedom Driver System. (September 18, 2015). Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology. Retrieved from https://www.dicardiology.com/content/syncardia-systems-issues-class-i-recall-freedom-driver-system

- Cook Medical Issues Global Recall of Beacon Tip Angiographic Catheter Products. (August 11, 2015). Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology. Retrieved from https://www.dicardiology.com/content/cook-medical-issues-global-recall-beacon-tip-angiographic-catheter-products