Drug Administration Attributes

A drug’s intended use, including the frequency with which the drug is administered and the urgency of drug delivery, should also be driving factors in device selection. Users’ prior experience using such devices is also a key consideration. We describe these drug administration attributes and our experience below.

- Frequency. The best drug delivery device might differ based on use intervals (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly). For a drug delivered daily, users will likely value a device that has few set-up and administration steps, delivers drug in seconds, and minimizes disruption of their daily routine. That said, users are likely to become highly skilled at using a device they use daily, suggesting that they will eventually become adept at using a more complex device. By comparison, a device intended for more seldom, monthly drug administration should probably have a limited number of use steps (two to four), recognizing that users interact with the device infrequently and might need to intuit the steps if they cannot recall a multi-step administration process.

- Urgency. Drugs that must be delivered urgently, such as Epinephrine to someone experiencing anaphylaxis as a reaction to an allergen, should be paired with a device that facilitates rapid use, noting that near-immediate medication delivery is essential to ensure effectiveness. These users do not have time to read instructions or study the device to figure out how to operate it. Furthermore, users responding to an emergency can be stressed, have shaky hands, and be unfamiliar with the device. As such, emergency-use devices must enable quick—and safe and effective—use, regardless of factors that might hinder optimal use. Characteristics that facilitate rapid, successful drug delivery include a device with few use steps, no assembly, large non-slip grip surfaces, as well as conspicuous on-device instructions describing and/or illustrating key steps.

- User experience with the device. As previously suggested, some drug delivery device users might not have prior experience with a given device. For example, a passer-by might have to administer Epinephrine to a stranger experiencing a severe allergy attack in a park. Features such as clearly marked hazards (e.g., needle end), orientation cues indicating how to hold the device, and prominent instructions that convey the route of administration (e.g., subcutaneous injection, nasal spray), can all facilitate correct use by untrained and inexperienced users.

Device Characteristics

Users often express the need for specific device characteristics (e.g., highly portable) that will maximize the convenience of fitting the drug delivery device into their lives. Several device user interface characteristics should be considered during device review and selection.

- Portability. Devices that users must carry with them at all times, such as a rescue inhaler used to treat an asthma attack, should be optimized for such use. Portability rests on a device’s compactness, relatively low weight, durability, temperature stability, and safeguards against accidental actuation due to rough handling (e.g., storage in a child’s backpack that gets tossed around). If a device is truly portable, it is more likely the user will have it with him or her when the medication is needed.

- Discreetness. Some users will prefer to use a device with which they can interact discreetly—without drawing undue attention, such as during use in a restaurant, theater, classroom, athletic venue, etc. For example, some people with diabetes appreciate a device that enables them to deliver insulin during a public dinner without others noticing.

- Workload. Administering medication routinely can disrupt users’ lives in profound or insidious ways that equate to “treatment burden.” The extent to which users accept drug delivery devices with high treatment burden varies. The device selected for users who already have many treatment options (e.g., people with diabetes) should reduce treatment burden (e.g., make treatment faster, easier, less painful, less frequent). In contrast, it might be acceptable to select a device that that is somewhat inconvenient, intrusive, and/or time-consuming to use if the end-users have limited or no treatment options (e.g., people with a very rare condition) because it is their only option for treating or managing the symptoms of their condition.

Conclusion

Companies are well served to follow a drug delivery device selection process informed by user needs, capabilities and preferences. The process might lead them to an optimal device that users can easily integrate into their lives, ensuring safe and effective use as well as good compliance with the given therapy regimen. In lieu of a good selection process, companies might face an uphill battle when it comes time to validate their chosen drug delivery device. As such, a user-centered approach to device selection/design is a benefit to the end-users while also being good for business.

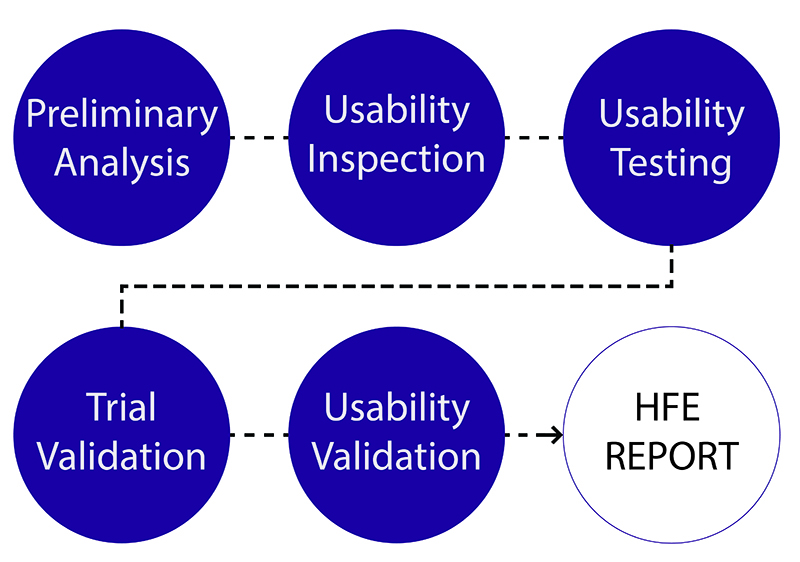

In a follow-up article, we will provide some advice regarding how companies can exercise due care when evaluating off-the-shelf drug delivery devices, assessing the extent to which human factors and an assessment of users’ needs was performed during device development.